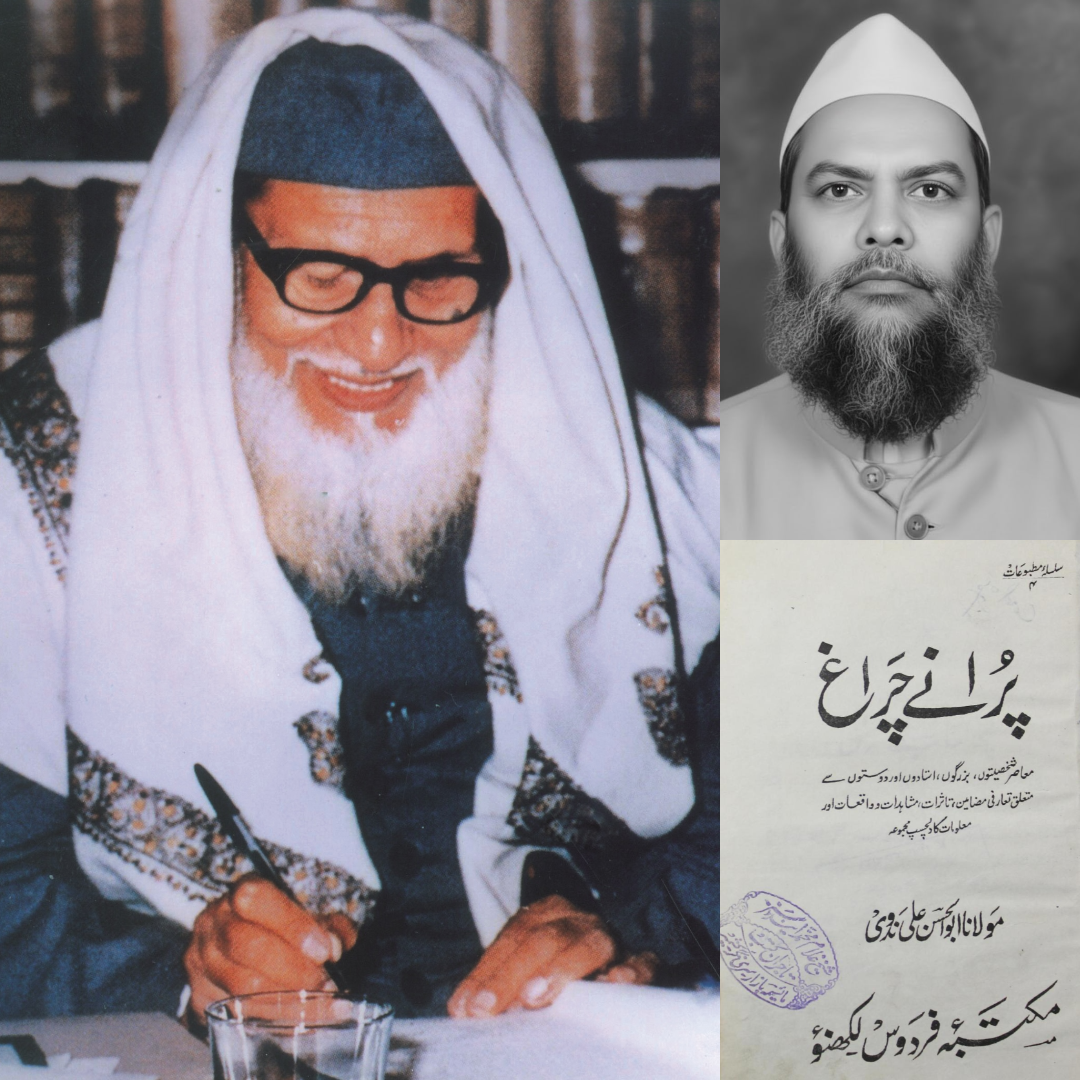

Purāne Chirāgh: Shaykh Owais Nagramī Nadwī

Purāne Chirāgh (“Old Lamps”) is a reflective biographical work by the esteemed Shaykh Abū al-Ḥasan ʿAlī Nadwī رحمه الله in which he records the lives, personalities, and spiritual impressions of a number of distinguished scholars, reformers, and elders whom he personally knew or observed. These “lamps” (چراغ) are presented as sources of nūr whose light illuminated their era and whose imprints remain instructive for future generations. The book is not a conventional historical chronicle. Rather, it is a deeply personal and literary portrayal of men who embodied ʿilm, taqwā, zuhd, daʿwah, and iṣlāḥ. Through elegant narrative and insightful analysis, the Shaykh captures their intellectual temperament, moral character, pedagogical methods, and spiritual influence.

The work also subtly documents the intellectual currents of the Indian subcontinent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly within the reformist and Ahl al-Sunnah scholarly milieu. The work combines adabī elegance with historical sobriety. It reflects the Shaykh’s hallmark qualities: emotional depth without exaggeration, reverence without blind hagiography, and critique without disrespect.

Across its three volumes, Purāne Chirāgh covers approximately forty (40) personalities. The following is a translation of the Shaykh’s entry of his friend and colleague of nearly 4 decades, Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Nagramī Nadwī رحمه الله

A Bond of Forty Years

When one takes up the pen to write about a companion and friend with whom a bond of fellowship endured, in one form or another, for nearly forty years, old wounds of the heart are reopened. A flood of memories surges forth in such profusion that one scarcely knows what to include and what to omit. Yet the heart insists, and the right of a dear and sincere friend demands, that this account be told in some manner. In the realm to which he has now departed, he is no longer in need of such remembrance. But in the world we inhabit, it is customary to soothe the grieving heart by recalling and recounting those who have passed on, and to acquaint those who knew little, or nothing, of them with their virtues and accomplishments. Perhaps for new entrants upon the path of knowledge, there may be in this account some lesson and some means of encouragement and inspiration.

During his long and painful illness, Shaykh Owis رحمه الله read my book Purāne Chirāgh with great relish and enthusiasm. Many of the personalities mentioned therein were common between us; many of those “lamps” were the very ones from whom both he and I derived equal light. Indeed, in the case of some of them, his association and lived experience were deeper than mine—for example, his shaykh and spiritual guide, Ḥaḍrat Maulānā Sayyid Ḥusain Aḥmad Madanī رحمه الله; his teacher and mentor, Maulānā Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله; and his dear friend—and in a sense, his disciple—Sayyid Ṣiddīq Ḥasan, I.B.S. Among the remaining figures, some had been his teachers, others his elders, and others his companions. On one occasion when I visited him, he expressed deep pleasure at reading the book and pointed out certain personalities whose mention, he felt, ought to have been included. Neither he nor I knew that the time for recounting his own life would arrive so soon.

Nagrām: A Land of Lamps

“Nagrām” is a renowned and distinguished township, famed for producing men of stature. Even during the Hindu period it was a major center of learning, and under Muslim rule as well, eminent personalities arose from its soil. It may be known to many that Sulṭān al-Mashāyikh Khwāja Niẓām al-Dīn Awliyāʾ, Maḥbūb-e Ilāhī رحمه الله’s beloved disciple—indeed, his khalīfah and successor—Ḥaḍrat Sayyid Naṣīr al-Dīn Chirāgh Dehlavī رحمه الله was the pride of a family of Sādāt from this very town and its environs. Later, in the twelfth century Hijrī, when the Chishtī-Niẓāmī silsilah was as though a lamp at dawn, it was rekindled with great brilliance by Ḥaḍrat Shaykh Niẓām al-Dīn Aurangābādī رحمه الله (khalīfah of Ḥaḍrat Shāh Kalīmullāh Jahānābādī رحمه الله and the illustrious father of Ḥaḍrat Shāh Fakhr Dehlavī رحمه الله), who likewise traced his origin to this land.

Toward the end of the thirteenth century Hijrī, Allāh illuminated this township with the lamp of guidance, rectification of beliefs, and reform. Although Awadh possessed numerous great spiritual and scholarly centers from which thousands, indeed, hundreds of thousands, received inward blessing and outward knowledge, in the sphere of reforming beliefs, correcting customs, and calling to tawḥīd and adherence to the Sunnah, two families stood as standard-bearers. One was the family of Ḥaḍrat Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd رحمه الله, whose center was in the district of Rae Bareli. The other was the family centered in Nagrām in the district of Lucknow.

From the former family, a shaykh of ṭarīqah and caller to Allāh, Maulānā Sayyid Khwāja Aḥmad Naṣīrābādī رحمه الله, was actively engaged in guidance and spiritual training at Naṣīrābād, with his influence extending far and wide. On the other side, in Nagrām, there was a God-conscious scholar and dāʿī of truth, Maulānā ʿAbd al-ʿAlī Ṣāḥib Tagramī (1296–1331 AH). In the outward sciences he studied under Maulānā ʿAbd al-Ḥakīm رحمه الله (grandson of Ḥaḍrat Baḥr al-ʿUlūm رحمه الله), and in sulūk and taṣawwuf he maintained spiritual affiliation with Qāḍī ʿAbd al-Karīm Nagrāmī رحمه الله. He was authorized and trained by his khalīfah, Gulzār Shāh Ṣāḥib Kashnawī رحمه الله. According to the author of Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir, he also received authorization in this silsilah of ʿilm ilāhī from Ḥaḍrat Maulānā Sayyid Khwāja Aḥmad Ṣāḥib Naṣīrābādī رحمه الله. Owing to unity in outlook and temperament, these two great contemporaries shared deep, sincere, and brotherly relations. Both were eminent exponents of the Sunnah and eradicators of bidʿah. The spirit of tawḥīd and Sunnah and the reformist colour visible in many towns of these regions, including Rae Bareli and Lucknow districts, were the fruits of their efforts.

A Lineage of Scholarship and Reform

Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAlī Nagramī Ṣāḥib رحمه الله was also a scholar of high standing. He studied with Maulānā Anwar ʿAlī Murādābādī رحمه الله and Shaykh Awḥad al-Dīn Bilgrāmī رحمه الله. A work of his on Aḥkām al-Qurʾān has been published, and the late Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله intended to expand and complete it—evidence of his own scholarly maturity and experience. He authored numerous treatises refuting prevalent customs. Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله would often recount with evident delight an account of a debate in which the opposing side was represented by Maulvī Alif Khān Rae Bareilvī. Due to Maulānā ʿAbd al-ʿAlī Ṣāḥib’s incisive scholarly objections, raised at nearly every sentence, his opponent was rendered speechless.

Shaykh ʿAbd al-ʿAlī Ṣāḥib’s son (the grandfather of Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله), Shaykh Muḥammad Walīs Ṣāḥib Nagrāmī رحمه الله (1275–1330 AH), was a student of Fakhr al-Mutaʾakhkhirīn Maulānā ʿAbd al-Ḥayy Ṣāḥib رحمه الله and a disciple of Shaykh Faḍl al-Raḥmān Ṣāḥib Ganj Murādābādī رحمه الله. He was a distinguished scholar and man of letters. At the request of Shaykh Sayyid Muḥammad ʿAlī Mongerī رحمه الله, Nāẓim of Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ, he compiled biographical notices of contemporary scholars under the title Tatbīb al-Ikhwān bi Dhikr ʿUlamāʾ al-Zamān, reflecting his breadth of heart and sound temperament. The author of Nuzhat al-Khawāṭir mentions thirteen of his works, mostly dealing with issues in fiqh and ḥadīth.

His son, Shaykh Muḥammad Anīs Nagramī Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, possessed deep insight in fiqh and refined familiarity with the works of Shaykh Shāh Walī Allāh رحمه الله, Shāh ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz رحمه الله, Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله, and ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Qayyim رحمه الله. In creed and method, he was an adherent and advocate of that Ahl al-Sunnah school whose imams in India included Shaykh Mujaddid Alf Thānī رحمه الله, Shaykh Shāh Walī Allāh Dehlawī رحمه الله, and finally Shaykh Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd رحمه الله and his jamāʿah.

Within this family, scholarly temperament and attachment to the people of truth remained constant. Many individuals earned recognition due to their literary or daʿwah-oriented inclinations, including Maulvī Muḥammad Aḥsan Ṣāḥib Waḥshī Nagrāmī رحمه الله, Shaykh Maḥfūẓ al-Raḥmān Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, and Deputy ʿAlī Muttaqī Ṣāḥib رحمه الله. However, the personality who most illuminated this family’s name in later times was the prematurely deceased and accomplished Shaykh ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Nagrāmī Nadwī رحمه الله.

Shaykh ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Nagrāmī رحمه الله: A Lost Radiant Pearl

Through him, not only this family and township but also the institution and scholarly circle that had the honour of educating him gained distinction. Upon his demise, Shaykh Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله wrote a deeply moving article in Maʿārif entitled: “Hamārī Jamāʿat kā Gohar-e Shab-Chirāgh Gum Ho Gayā.”

Allāh had endowed this young scholar with remarkably diverse qualities. He was a mufassir, litterateur, stylist, eloquent orator, successful teacher, and beloved instructor. At the same time, he was a valiant rider in the field of siyāsah and ḥurriyyah, one who openly invited the gallows and the noose.

Shaykh Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله and his institution took pride in him, and he was also a close associate of Shaykh Abū al-Kalām Āzād رحمه الله. He was a disciple—and, if reports are correct, an authorized representative—of Ḥaḍrat Shaykh al-Hind Maulānā Maḥmūd Ḥasan Ṣāḥib رحمه الله. Allāh had placed in his personality and speech a remarkable spiritual warmth. During my student days at Dār al-ʿUlūm, I did not see students so devoted to any teacher as his students were to him.

It is a matter of sorrow that his life did not extend further, and he departed from this transient world at the age of twenty-seven or twenty-eight. Had he lived, and had Allāh so willed, he would have been seen at the highest summits of religious and scholarly distinction. The aforementioned Shaykh ʿAbd al-Raḥmān Nagramī Ṣāḥib رحمه الله was the maternal cousin of Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib Nadwī رحمه الله.

Early Association and Formative Companionship

Shaykh Maṭlūb al-Raḥmān Ṣāḥib Nadwī رحمه الله and Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib Nadwī رحمه الله were both luminous scions of this same family. The former was my classmate, and it was most likely through him that my acquaintance with Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله first began. He was one or two years younger than I. When this association commenced, I was in the seventh year at Dār al-ʿUlūm, while he was a student in the sixth year—this was around 1930.

Because of longstanding family ties, and in addition to the relationships already mentioned (for the Shaykh’s father, Shaykh Muḥammad Anīs Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, had studied under my respected father, Shaykh Sayyid ʿAbd al-Ḥayy رحمه الله), our connection naturally deepened.

This was during the period when my elder brother, Shaykh Ḥakīm Dr. Sayyid ʿAbd al-ʿAlī Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, was effectively overseeing the administration. I say “effectively” because although the official Nāẓim was Nawāb Sayyid ʿAlī Ḥasan Khān Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, most of the practical work was carried out by my brother. Due to familial relations, both through the Nāẓim of Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ and because my brother was the city physician, the members of this family frequently visited our residence.

At that time, on the left side while proceeding from Naẓīrābād toward Qaisar Bāgh, there stood an upper-storey residence which served as the family’s lodging in Lucknow. It was popularly known as “Nagrām House.” While going to and returning from Nadwah, Mawlawī Maṭlūb Ṣāḥib or Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله would often visit there. Occasionally, Shaykh Muḥammad Anīs Ṣāḥib رحمه الله would also be present and would receive us with elder-like affection.

When Shaykh Sayyid Ḥusain Aḥmad Madanī رحمه الله began residing at our home on Goen Road, their visits increased considerably. Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله soon established a bond of iṣlāḥ and tarbiyah with Ḥaḍrat, and ultimately he was honoured with ijāzah.

My late brother had been observing him from the beginning. His discerning eye had recognized his worth early on. Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله would repeatedly express deep gratitude that it was Dr. Ṣāḥib who first directed his attention to the works of the Shaykhayn: Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله and ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Qayyim رحمه الله. He even mentioned this in the introduction to his book al-Tafsīr al-Qayyim.

Whenever he spoke of my brother, his eyes would often moisten and his voice become choked with emotion. He regarded him among his earliest scholarly and religious patrons and would fondly recount his kindnesses and attentions. At such moments, there would be a visible glow in his eyes and a radiance of gratitude upon his face.

Intellectual Taste and Scholarly Formation

During our student days, and later when we were both attached to the teaching faculty at Dār al-ʿUlūm, opportunities for close companionship increased. We would often go for morning walks together. At that time, the Shaykh رحمه الله was physically frail and lean, frequently ill, and under my brother’s medical care.

Even then, his passion for study was evident. Besides the works of the Shaykhayn and the writings of Shāh Walī Allāh رحمه الله and his scholarly lineage, he read widely in every branch of knowledge—scholarly, literary, historical, and investigative works.

A refined intellectual temperament, cultural breadth, general awareness, and eloquence in speech and writing were part of his familial inheritance. They were also fruits of the refined culture of Awadh and the education of Nadwah. He was free from dryness and narrow-mindedness; thus, in any gathering of friends he never appeared alien or out of place. He participated in every scholarly and literary discussion without ever becoming burdensome.

Training under Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله

Because of his intellectual inclination and broad reading, he soon gained special closeness in the gatherings of Shaykh Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله. Sayyid Ṣāḥib رحمه الله greatly valued capable graduates of Dār al-ʿUlūm and wished for their scholarly and literary abilities to mature so that they might emerge as teachers, authors, and representatives of truth, occupying the positions of their elders.

His discerning gaze fell upon Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله. He summoned him to Dār al-Muṣannifīn and personally undertook his training.

Few in India realize that although Sayyid Ṣāḥib رحمه الله is widely known as a historian and litterateur, and some still insist on describing him solely in those terms, yet, as I wrote in Purāne Chirāgh, in my view his primary field of distinction was the understanding of the Qurʾān and ʿIlm al-Kalām.

I did not have the honour of meeting Shaykh Ḥamīd al-Dīn Farāhī رحمه الله, whose depth in Qurʾānic reflection is acknowledged. But within my limited knowledge, after him, I see none equal to Sayyid Ṣāḥib رحمه الله in tadabbur al-Qurʾān, in grasping its rhetorical, literary, and theological subtleties, and in diving deep into its meanings.

This statement is not born of factional loyalty or mere devotion. I personally heard many of his Qurʾānic lessons and discourses. On several occasions he would attend my Qurʾān lecture at Dār al-ʿUlūm and begin speaking, sometimes continuing uninterrupted for two or three hours. Once, when we visited him in Aʿẓamgarh during his recovery from a prolonged illness, he delivered a discourse on Sūrat al-Jumuʿah. I have not heard a more profound, coherent, and thought-provoking exposition of the Qurʾān.

Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله benefited especially from him in Qurʾānic studies and in kalām and ʿaqīdah. It is fair to say that among the later graduates of Dār al-ʿUlūm, none had the opportunity to benefit from Sayyid Ṣāḥib رحمه الله in these two disciplines so extensively, systematically, and comprehensively. Thus, he may rightly be called his true student in these fields, a gleaner from his harvest of excellence.

This distinction ultimately led to his selection for the chair of Tafsīr at Dār al-ʿUlūm, as both the Nāẓim of Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ and its responsible authorities recognized his superiority in this noble discipline.

Defense of Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله

The Shaykh’s attachment to Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله and his intellectual school reached the level of deep devotion. He could not tolerate unjust criticism against him.

A particularly delicate moment arose when, despite knowing that his beloved shaykh, Ḥaḍrat Maulānā Sayyid Ḥusain Aḥmad Madanī رحمه الله, did not hold Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله in high esteem, he wrote a forceful and well-argued article defending him against unfair attacks by a learned critic. This article was published in al-Furqān.

He undertook this step despite the risk of displeasing his shaykh, a significant trial for a devoted and obedient murīd. He discharged this delicate responsibility with great skill and composure and received wide appreciation from those who recognized the stature of Imām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله.

It was due to his sincerity and dignified style that, to my knowledge, no estrangement occurred between him and Maulānā Madanī رحمه الله.

His Engagement with Taṣawwuf

Among his contemporaries, another distinguishing feature was his deep study of the literature of Taṣawwuf. He firmly believed in the harmony between Taṣawwuf and Sharīʿah and possessed special ability in demonstrating this concord.

An excellent example is his scholarly article included in Shaykh Manẓūr Nuʿmānī’s رحمه الله edited volume Taṣawwuf Kyā Hai? This article successfully removed intellectual confusions and played a notable role in dispelling unwarranted fear toward Taṣawwuf.

In this field, he particularly valued two works:

- Irshād al-Ṭālibīn by Qāḍī Thanāʾ Allāh رحمه الله.

- Ṣirāṭ al-Mustaqīm, a collection of the sayings and discourses of Ḥaḍrat Sayyid Aḥmad Shahīd رحمه الله.

He often recommended these works to students and sometimes even taught them. It is regrettable that illness and teaching responsibilities prevented him from undertaking major scholarly work on them.

His Mastery in Tafsīr

Tafsīr was his special field, and his insight in it continued to expand steadily. It is difficult to imagine that any significant work in the Tafsīr collection of Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ’s library escaped his attention. For a long time he eagerly awaited the publication of Tafsīr al-Qurṭubī. When it finally became available, he studied it with great enthusiasm. He also acquired and studied with dedication certain tafāsīr not yet widely circulated in India, such as Tafsīr al-Qāsimī by ʿAllāmah Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī رحمه الله.

Among Urdu works, he held Shaykh ʿAbd al-Mājid Daryābādī’s رحمه الله Tafsīr al-Mājidī in high regard and recommended it to his students. He was also a devoted admirer and advocate of Shāh Walī Allāh Dehlawī’s رحمه الله celebrated work al-Fawz al-Kabīr fī Uṣūl al-Tafsīr. He authored valuable annotations on it, later published in Lahore by Maktabah Salafiyyah under the supervision of Maulānā ʿAṭāʾ Allāh Ḥanīf رحمه الله.

Few, in my view, were as capable as he in clarifying its concise and compact arguments. He also added beneficial annotations to Shāh Walī Allāh’s رحمه الله treatise al-ʿAqīdah al-Ḥasanah, published as al-ʿAqīdah al-Sunniyyah by Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ Press and incorporated into its curriculum.

Internationally, his most significant introduction came through his Arabic work al-Tafsīr al-Qayyim, in which he systematically gathered the dispersed exegetical material found across the vast corpus of ʿAllāmah Ibn al-Qayyim رحمه الله. This book was published in elegant Arabic type by Maṭbaʿat al-Sunnah al-Muḥammadiyyah and was warmly received in Saudi Arabia, Najd, and Ḥijāz. He had intended to compile a similar work collecting the Qurʾānic discussions and research of Shaykh al-Islām Ibn Taymiyyah رحمه الله. A substantial portion had likely been prepared, but publication never materialized.

Likewise, he intended to supervise scholarly works on Qurʾānic rhetoric (Balāghat al-Qurʾān) and Qurʾānic grammar (Naḥw al-Qurʾān), guiding his students in their preparation. However, persistent ill health deprived him of this opportunity.

His Weekly Qurʾānic Dars in Lucknow

In addition to his long-standing service to the Qurʾān at Dār al-ʿUlūm Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ, where his primary audience consisted of advanced students, there existed another vast and influential arena of his Qurʾānic service. This was the weekly dars in the city attended by distinguished Muslims, senior government officials, and highly educated English-speaking elites.

The foundation of this gathering was laid by our respected friend, Sayyid Ṣiddīq Ḥasan, I.B.S., Sir Member of the Board of Revenue, Lucknow. The dars was held regularly every Saturday after Maghrib at his residence, and it continued for many years. Even after Sayyid Ṣāḥib’s demise in 1963, the gathering remained established at the same residence. The “cream” of officers and senior administrators with a taste for Qurʾānic study would attend. All were convinced of the Shaykh’s breadth of vision, his sensitivity to modern intellectual concerns, and his ability to address new forms of doubt.

Among those present, I did not see anyone more widely read or possessing greater scholarly refinement than Shaykh Ẓuhūr al-Ḥasan Ṣāḥib, former Revenue Secretary of the Government of Uttar Pradesh. He attended regularly. One day he remarked to me that Shaykh Muḥammad Owais Ṣāḥib رحمه الله had attained remarkable distinction and competence at such a young age, and that his rank in understanding the Qurʾān was exceedingly high.

Through this gathering, a genuine interest in reading and understanding the Qurʾān developed among the educated circles of the city. The Shaykh رحمه الله enjoyed great moral authority and intellectual prestige within this class, and many people in need benefited through him. On numerous occasions I myself sought his assistance in such matters, and the needs of deserving individuals were fulfilled.

Regrettably, this blessed series was interrupted due to his prolonged and complicated illness, which lasted nearly two years. Until the very end, his students, friends, and attendees felt deep anguish over its cessation.

Broadness Beyond Partisanship

Although the Shaykh رحمه الله was entirely a product of Dār al-ʿUlūm Nadwat al-ʿUlamāʾ and, in spiritual training, a devoted disciple of Ḥaḍrat Maulānā Sayyid Ḥusain Aḥmad Madanī رحمه الله, whose political outlook he also followed, he was free from narrowness and factionalism.

He held Ḥakīm al-Ummah Ḥaḍrat Maulānā Ashraf ʿAlī Thānawī رحمه الله in high esteem and fully acknowledged the value and results of his reformative and spiritual efforts. During his stays in Lucknow, he would attend his gatherings with humility and devotion and maintained correspondence with him. He also enjoyed deep relations with many of Ḥaḍrat’s khulafāʾ.

Among his close relations was Mawlawī Najm Aḥsan Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, one of Ḥaḍrat’s disciples, who lived for a long time in Pratapgarh and recently passed away in Karachi. Among his own associates were Shaykh ʿAbd al-Mājid Daryābādī رحمه الله, Shaykh ʿAbd al-Bārī Nadwī رحمه الله, and Shaykh Masʿūd ʿAlī Nadwī رحمه الله, with whom he maintained sincere and affectionate ties. Shaykh Sayyid Sulaimān Nadwī رحمه الله, of course, was his beloved teacher and mentor.

Whenever Ḥaḍrat Maulānā ʿAbd al-Qādir Rāypūrī رحمه الله visited Lucknow and stayed for weeks at Dār al-ʿUlūm or the city’s tablīghī center, the Shaykh رحمه الله would attend his gatherings with such consistency and devotion that an observer might assume him to be among his foremost disciples.

He held deep reverence for Shaykh al-Ḥadīth Maulānā Muḥammad Zakariyyā Ṣāḥib رحمه الله, and the Shaykh likewise held him in affectionate regard. Upon his passing, the Shaykh expressed profound sorrow and grief.

Sincerity, Generosity, and Moral Courage

The Shaykh رحمه الله rejoiced sincerely in the happiness of his friends. He was large-hearted in expressing appreciation and recognition. If he approved of one of my books, he would praise it openly and encourage his friends and students to read it. This was a clear sign of his sincerity.

Likewise, if any tragedy befell those connected to him, he would grieve as a close relative would, personally sharing in their sorrow. If he heard of someone’s success, he would offer heartfelt congratulations. Toward the children of his extended family, he behaved like a benevolent elder—offering useful guidance and reproving laziness or poor taste. These were qualities characteristic of the refined nobility of earlier times.

On one occasion, during a gathering at Sulaimāniyyah Hall held in honour of visiting Arab guests, I stated clearly in my speech that we Indian Muslims have not tied our destiny and religious future to the Arabs, nor are we bound to follow them blindly in whatever path, right or wrong, they may adopt. Our Islam and religiosity are not conditional upon theirs. Our relationship is directly with Allāh, with the dīn and sharīʿah He has granted, and with the Messenger He has sent.

The Shaykh رحمه الله was so pleased by this address that he rose during the session and publicly expressed his love and appreciation. Only one endowed by Allāh with sincerity, affection, and moral courage could have acted thus.

Illness, Passing, and Burial

It is a matter of deep sorrow that just when his scholarly and educational benefits were flowing abundantly, when he was steadily ascending the ranks of intellectual and religious distinction, and when it seemed that, at least in India, he might become a central authority in the sciences of the Qurʾān during this era of scarcity of men, his illness began.

Initially it was thought to be angina (wajʿ al-fuʾād). Soon complications arose. He was repeatedly admitted to the Medical College and discharged home, yet the illness progressed despite treatment. No effort was spared in his medical care. This continued for two years. His appetite vanished completely. Severe insomnia afflicted him. Food intake became negligible, taken almost as medicine. Weakness reached such a degree that even sitting and standing became difficult.

Yet the nearness of death did not appear imminent. This state had continued for months, and those bound to him by love had not lost hope. Then, on 29 Shaʿbān 1391 AH, between Ẓuhr and ʿAṣr, the appointed hour arrived, and he returned his soul to its Creator. That very evening the moon of Ramaḍān was sighted, a month for which he always had special reverence. On the morning of 1 Ramaḍān, Shaykh Muḥammad Manẓūr Nuʿmānī رحمه الله personally performed his ghusl in complete conformity with the Sunnah. Those who knew his care in such matters considered fortunate the one whose body he washed.

I was away in Delhi and Sahāranpūr due to urgent need. On the morning of 1 Ramaḍān, 28 August 1976, when I stepped onto the platform at Lucknow station at 9 a.m., I suddenly learned that the Shaykh had departed this transient world the previous day. The janāzah had already reached Aish Bāgh. For this companion, who for forty to forty-five years had shared friendship and fellowship with him, the final service of attending his janāzah remained. What recourse was there except patience, acceptance, and submission to the Divine decree?

At Aish Bāgh a large gathering of admirers, disciples, and associates had assembled. Soon this trust of Allāh was returned to Allāh, and this servant of the Qurʾān was consigned to the earth. He was indeed fortunate: the first day of Ramaḍān was granted to him. Shaykh Manẓūr Ṣāḥib رحمه الله stated that while performing the ghusl, his face appeared fresh and radiant; it did not seem as though he had endured such prolonged illness. He would say that this was a blessing of the Shaykh’s firmness in tawḥīd.

It is regrettable that in this age of intellectual decline and diminished resolve, filling the place left vacant by his passing appears exceedingly difficult. Students of the Qurʾānic sciences still had much to gain from him. Many scholarly works remained incomplete. Many of his intellectual aspirations remained unfulfilled.

As for us, his old companions and friends, what can we say except:

اے ہم نفسانِ محفل ما رفتید ولے نہ از دل ما

“O companions of our gathering, you have departed—but not from our hearts.”