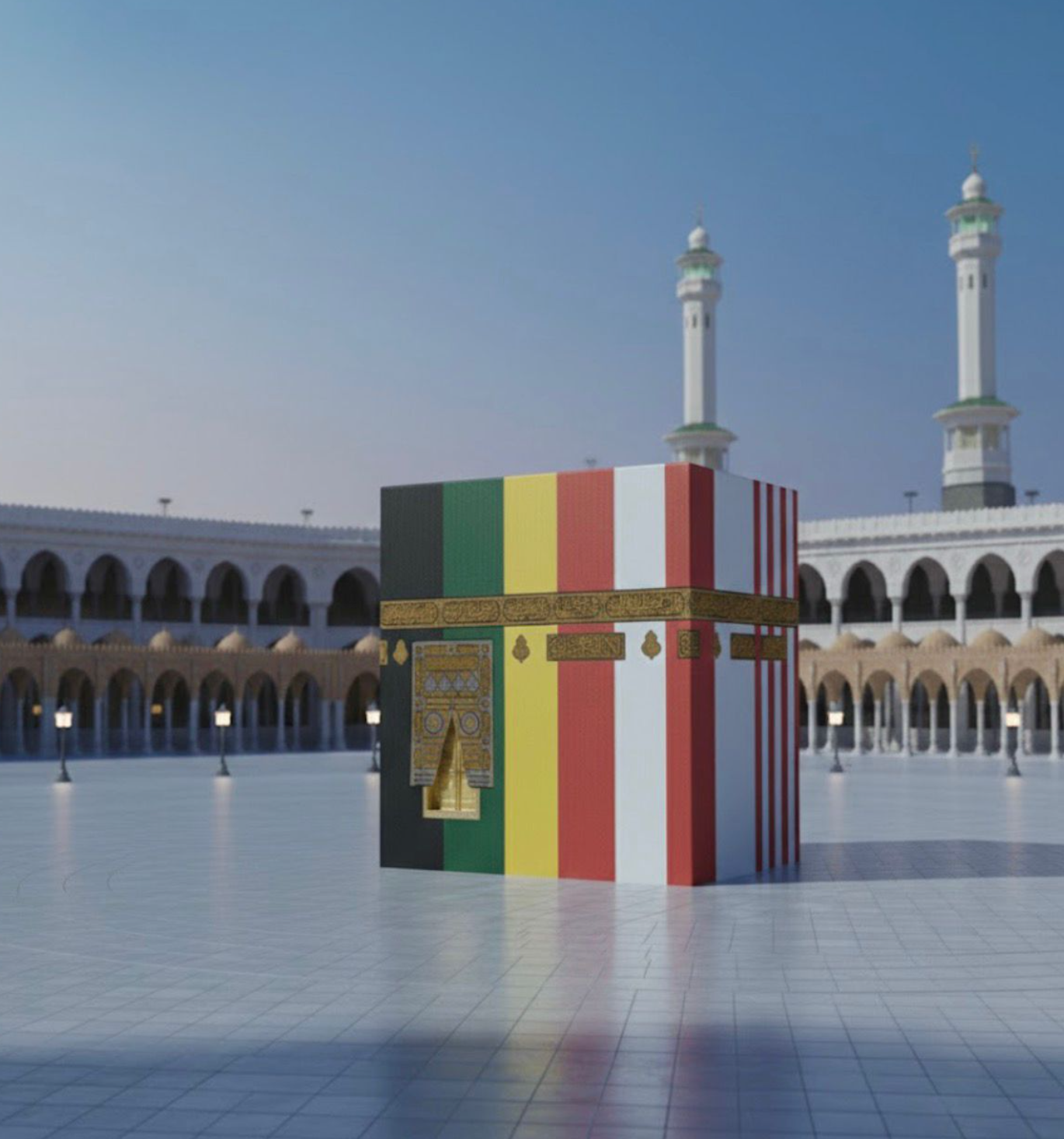

Many people assume that the Kiswah of the Ka‘bah has always been black, unchanged across time. History tells a different story. Over the centuries, the Ka‘bah has been clothed in different colours, fashioned from varied materials, and renewed in ways shaped by the customs, resources, and administrative realities of each era. Linguisitically, the term Kiswah is defined as, "That with which something is covered, whether a garment or otherwise.” [Lisān al-ʿArab] In our context, it refers to the cloth garment placed upon the Ka‘bah, whether leather, linen, or brocade, and regardless of colour. Far from being static, it reflects a rich and well-documented historical evolution. From early leather coverings and red-striped Yemeni cloths, to white Egyptian linen, red, green, yellow, and finally black brocade, the Kiswah tells a layered story of devotion, authority, and stewardship across Muslim history.

What started as an interesting discussion, to a sketch by my wife Zainab, to a 3D rendering of that image, gave birth to this article traces that journey, exploring how the Kiswah of the Ka‘bah gradually developed into the form recognised today.

Islamic historians record multiple early views regarding who first covered the Ka‘bah. It is reported that Prophet Ismā‘īl عليه السلام was the first to place a partial covering upon the Ka‘bah. Other authorities state that the first person to drape the Ka‘bah in a more recognisable and deliberate form was ‘Adnān ibn Uddād, an ancestor of the Prophet ﷺ.

The earliest figure consistently reported to have fully covered the Ka‘bah is the Himyarite king Abū Karib As‘ad, known as Tubba‘ al-Ḥimyarī of Yemen. Initially, he clothed the Ka‘bah with leather strips and coarse coverings (anṭā‘). He then replaced these with red, striped Yemeni garments, commonly identified with Ma‘āfir cloth, a renowned textile attributed to the region of Ta‘izz. He also made a door for the Ka'bah. This event is placed around nine hundred years before the advent of the Prophet Muḥammad ﷺ.

After the era of Tubba‘, covering the Ka‘bah came to be regarded as a religious duty and a great honour. The historians record that any individual who wished to cover it was permitted to do so, using whatever fabric they could afford. As a result, multiple coverings were often layered upon the Ka‘bah at the same time, to the extent that the structure was at times burdened by the excessive weight of accumulated cloth, necessitating later regulation and the removal of older Kiswahs. [Akhbār Makkah]

By the time of Qusayy ibn Kilāb, authority over the Ka‘bah and its associated functions had been consolidated under Quraysh. Among the notable pre-Islamic figures remembered in this context is al-Walīd ibn al-Mughīrah, a leading figure of Banū Makhzūm, and the father of Khālid ibn al-Walīd (رضي الله عنه). He was regarded as the wealthiest man of Quraysh. Ibn ‘Abbās reported that his estates and gardens stretched from Makkah to Ṭā’if, producing fruit throughout the year in both summer and winter. His annual income was described as immense, and he was known for lavish spending on pilgrims. The Quraysh collectively funded the replacement of the Kiswah in one year, while in another year al-Walīd alone financed its change, reflecting both his wealth and the prestige attached to providing the covering of the Ka‘bah.

Another significant pre-Islamic episode concerns Natīlah bint Janāb, the mother of al-‘Abbās ibn ‘Abd al-Muṭṭalib (رضي الله عنه). When al-‘Abbās was lost as a child, she vowed that if he were returned to her, she would cover the Ka‘bah with silk and brocade (dibāj). After he was safely found, she fulfilled her vow. For this reason, she is remembered as the first person to place a covering of silk and brocade over the Ka‘bah, and notably, the first woman to do so. [Fatḥ al-Bārī]

At the Conquest of Makkah in 8 AH / 630 CE, the Ka‘bah was still covered with the cloth of the polytheists. The Messenger of Allah ﷺ did not immediately replace this covering, and it remained in place during the earliest days following the Conquest. Shortly thereafter, a woman attempted to perfume the Ka‘bah with incense, causing the existing covering to catch fire. The burned Kiswah was removed and replaced with wasaʾil, a Yemeni red and white striped garment. [Akhbār Makkah]

During the era of the Rightly Guided Caliphs (mid-1st century AH / 7th century CE), the covering of the Ka‘bah entered a phase of order and regularity, reflecting the broader administrative discipline of the early Islamic state. After the passing of the Prophet ﷺ, the responsibility of maintaining the Kiswah fell under the authority of the caliphs, and it was no longer left to individual initiative alone. It is firmly reported that Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq (r. 11–13 AH), ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb (r. 13–23 AH), and ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān (r. 23–35 AH) (رضي الله عنهم) all clothed the Ka‘bah with qibāṭī, a fine, thin white linen woven in Egypt, named after the Copts (al-Qibṭ) who produced it. ‘Umar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb is reported to have written specifically to Egypt, instructing that the cloth be woven there and sent to Makkah for the Ka‘bah with the costs being borne from the Bayt al-Māl (public treasury). When removed, the cloth was distributed in charity rather than discarded. [Akhbār Makkah]

In the same period, it is reported that Shaybah al-Ḥajabī (the custodian of the Ka‘bah) entered upon ʿĀʾishah (رضي الله عنها) and said, “The coverings of the Ka‘bah accumulate with us and become many, so we remove them and dig a pit, deepen it, and bury them, so that they will not be worn by a menstruating woman or one in a state of major ritual impurity.” ʿĀʾishah (رضي الله عنها) said, “What you have done is wrong. Rather, sell them and place their price in the path of Allah and among the poor. For once they are removed from it, it does not harm who wears them, whether menstruating or in a state of impurity.” [Fatḥ al-Bārī]

Later, during the early Umayyad period (mid-1st century AH / late 7th century CE), Muʿāwiyah ibn Abī Sufyān (r. 41–60 AH / 661–680 CE) introduced a level of organisation and regularity in the covering of the Ka‘bah that had not existed before. Rather than renewing the Kiswah sporadically, he established a fixed annual schedule, under which the Ka‘bah was covered twice each year. It would be clothed with brocade (dibāj) on the Day of ‘Āshūrā’, and then reclothed with qibāṭī, the fine white Egyptian linen, at the end of the month of Ramaḍān, in preparation for ‘Īd al-Fiṭr. Mu‘āwiyah became the first caliph to order the complete removal of the coverings of the Ka'bah. Prior to that, its coverings were placed one over another, layer upon layer.

Muʿāwiyah did not confine his attention to the cloth alone. He also arranged for the regular perfuming of the Ka‘bah, assigning a set allotment of perfume for every prayer. In addition to this daily practice, he would send perfumes, incense burners (majāmir), and khalūq during the pilgrimage season, and again in the month of Rajab, ensuring that the House remained scented throughout the year. Beyond the Kiswah and its perfuming, Muʿāwiyah further formalised its care by appointing servants for the Ka‘bah, dispatching them specifically to attend to its maintenance and service. [Akhbār Makkah]

It is also reported that the first person to clothe the Ka‘bah with brocade (dibāj) as a full covering was ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr (رضي الله عنه) during his rule (64–73 AH / 683–692 CE) in Makkah. This occurred at a moment of political independence, when Ibn al-Zubayr had established his authority over the Ḥaram and undertook major works connected to the Ka‘bah, including its reconstruction upon the foundations of Ibrāhīm عليه السلام. Imam Ibn Ḥajar records that the distinction attributed to Ibn al-Zubayr lies not merely in the incidental use of brocade, which had appeared earlier in limited forms, but in making brocade the principal and complete Kiswah of the Ka‘bah. [Fatḥ al-Bārī]

Some reports state that ʿAbd al-Malik ibn Marwān (r. 65–86 AH / 685–705 CE) was the first to establish brocade (dibāj) as a consistent and continuous full covering of the Ka‘bah. According to these accounts, while brocade had appeared earlier—most notably during the rule of ‘Abd Allāh ibn al-Zubayr (رضي الله عنه)—it was under ‘Abd al-Malik that brocade became the standard Kiswah, renewed regularly and maintained without interruption. This policy was implemented on the ground by ‘Abd al-Malik’s governor in Makkah, al-Ḥajjāj ibn Yūsuf, who oversaw the affairs of the Ḥaram on behalf of the caliph. [Fatḥ al-Bārī]

During the Abbasid period, the Kiswah became increasingly ceremonial. It is reported that al-Maʾmūn ibn Hārūn al-Rashīd (r. 198–218 AH / 813–833 CE) was the first to clothe the Ka‘bah with white brocade as a full covering. Under al-Ma’mūn, the Ka‘bah was adorned with multiple coverings within a single year, including red brocade in Dhū al-Ḥijjah, white qibāṭī in Rajab, and white brocade in Ramaḍān. [Akhbār Makkah] The Ka‘bah thus appeared in different garments as the year progressed, each reflecting the spiritual character of the season.

Later, during the Abbasid period, the Caliph Jaʿfar al-Mutawakkil ʿalā Allāh (r. 232–247 AH / 847–861 CE) was informed that the red brocade covering of the Kaʿbah did not last until the month of Rajab, for it wore out quickly due to people touching it and rubbing themselves against the Kaʿbah. Upon receiving this report, al-Mutawakkil took measures to preserve the Kiswah and extend its lifespan. He ordered that additional izārs be added alongside the original one, and that the inner brocade garment (qamīṣ) be lengthened and let down until it reached the ground, so that direct contact would fall upon it instead of the outer covering.

He further arranged that the Kaʿbah be covered with successive izārs, with one new izār applied every two months, establishing a regulated cycle of renewal. This system was implemented in the year 240 AH for the covering of the following year. After observing the arrangement, the custodians of the Kaʿbah found that a single izār, together with the extended lower portion of the qamīṣ, was sufficient. They reported this to the Caliph, and from then on one izār would be sent, to be applied after three months, while the trailing hem would serve for the remaining period. [Akhbār Makkah]

It is further reported that Muḥammad ibn Sabuktakīn, the founder of the Ghaznavid dynasty, clothed the Ka‘bah with yellow brocade, representing a rare and short-lived variation in the colour of the Kiswah. Despite not being linked to the Abbasids, his patronage extended to the Ḥaramay. [Fatḥ al-Bārī] This episode illustrates that, during this period, the colour of the Kiswah had not yet been fixed permanently and could still change according to the patronage and initiative of individual rulers.

During the later Abbasid period, a decisive development took place. The Caliph al-Nāṣir li-Dīn Allāh (r. 575–622 AH / 1180–1225 CE) clothed the Ka‘bah with green brocade at the beginning of his caliphate, marking a departure from the earlier alternation between red and white brocade that had characterised previous Abbasid practice. This was later replaced with black brocade, after which the matter settled upon black as the standard colour. From this period onward—conventionally dated to the early 7th century AH / early 13th century CE—the Kiswah of the Ka‘bah has remained black, a practice that continues to this day. [Shifāʾ al-Gharām]

Kings and rulers continued to take turns in providing the Kiswah until a more permanent financial arrangement was established under al-Ṣāliḥ Ismāʿīl ibn al-Nāṣir, who in 743 AH / 1342–1343 CE endowed for the Kiswah a village from the environs of Cairo known as Bīsūs. He had purchased two-thirds of it from the agent of the Bayt al-Māl and then endowed the entirety of it for this purpose. Through this endowment, the Kiswah continued to be provided on a stable footing for many years. This arrangement remained in effect until the reign of al-Malik al-Muʾayyad Shaykh, who, in one year due to the weakness of the endowment, clothed the Ka‘bah from his own funds. He then entrusted the administration of the Kiswah to the judge Zayn al-Dīn ʿAbd al-Bāsiṭ, who devoted exceptional care to perfecting it, refining its workmanship to such a degree that its beauty was said to defy adequate description. [Fatḥ al-Bārī]

During the Fatimid period (4th–6th century AH / 10th–12th century CE), the manufacture and dispatch of the Kiswah became firmly institutionalised in Egypt. The Fatimid caliphs regarded the Kiswah as a visible symbol of their religious and political authority over the Ḥaramayn, and they oversaw its production in Egypt before sending it annually to Makkah as part of the official ḥajj caravan (maḥmal). From this period onward, Egypt emerged as the primary centre for the weaving, financing, and ceremonial dispatch of the Kiswah, a role it would retain for many centuries.

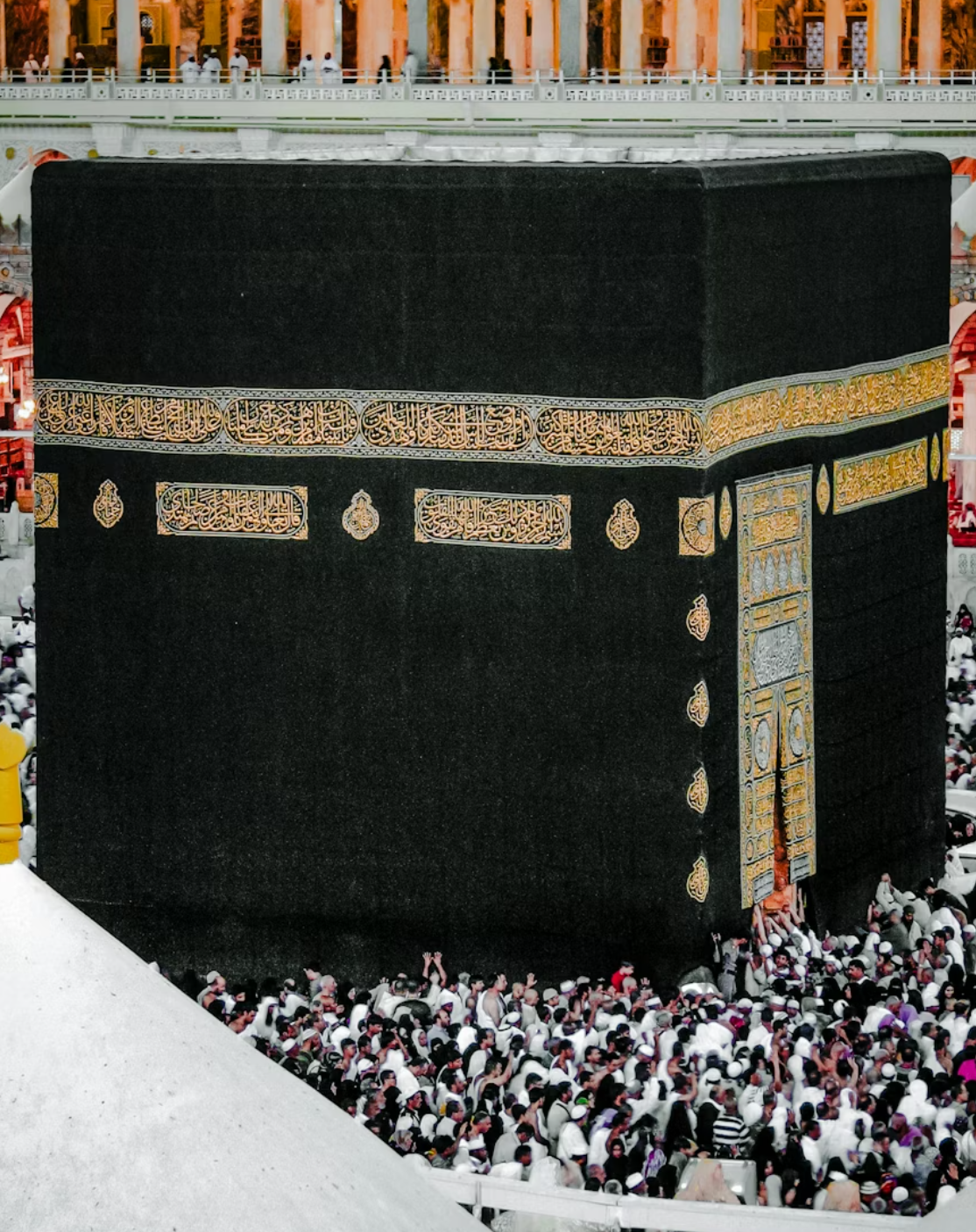

This established tradition was preserved and further strengthened under the Mamluk sultans (7th–10th century AH / 13th–16th century CE). The Mamluks not only retained the Egyptian manufacture of the Kiswah but elevated it into a highly formalised state institution. Dedicated workshops were established in Cairo, and the Kiswah was dispatched annually with great ceremony, accompanied by the maḥmal, which symbolised the sultan’s guardianship of the Sacred House. During this period, the Kiswah was consistently produced from black brocade, following the standardisation that had already taken place, and was richly embroidered with Qurʾānic inscriptions.

When Egypt was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire in 923 AH / 1517 CE, the Ottomans retained the existing Egyptian system rather than dismantling it. Although the Ottoman sultans assumed the title of Custodians of the Two Holy Sanctuaries, they continued to rely on Cairo as the centre for producing the Kiswah. Throughout the Ottoman period, the Kiswah was woven in Egypt, dispatched annually with the Egyptian ḥajj caravan, and ceremonially installed on the Ka‘bah in Makkah.

A major transition occurred in the modern era. In 1346 AH / 1927 CE, King ʿAbdulaziz ibn Saud established the first Saudi Kiswah factory in Makkah, well before Egypt ceased its role in supplying the Kiswah in 1962 CE. For a period, Egyptian and Saudi-produced Kiswahs coexisted, until production was fully consolidated in Makkah. Under King Faisal ibn ʿAbdulaziz, the factory was renovated and relocated to Umm al-Jūd in 1392 AH / 1972 CE, modernising its facilities and expanding its capacity. A few years later, it was formally inaugurated in Rabīʿ al-Ākhir 1397 AH / 1977 CE by King Fahd ibn ʿAbdulaziz, then Crown Prince.

From that point onward, the manufacture of the Kiswah became entirely local, carried out in Makkah under Saudi administration. With this development, the Kiswah entered its modern phase: produced annually in Makkah and embroidered with gold and silver threads shoacsing intricate Arabic callipgraphy. On the 25th of Dhū al-Qaʿdah, the Kiswah is raised and removed from the walls of the Ka‘bah, leaving the structure uncovered for a short period. In Makkah, this interval is traditionally described with the expression “al-Ka‘bah tuḥrim”, meaning that the Ka‘bah has entered a state akin to iḥrām, as its walls stand bare in preparation for the rites of Ḥajj. The Ka‘bah remains uncovered until the 9th of Dhū al-Ḥijjah (the Day of ʿArafah), when the newly woven Kiswah is installed. This is done while the pilgrims are gathered at ʿArafāt, ensuring minimal congestion in the Ḥaram. The new Kiswah then remains in place for the entirety of the coming year, until the cycle is repeated the following season. The removed Kiswah is then cut into pieces and distributed according to official protocols (as gifts, to institutions, or preserved for archival purposes). In recent years, the ceremony of changing the Kiswah has been scheduled on the first day of Muḥarram, marking the start of the new Hijri year.

.png)